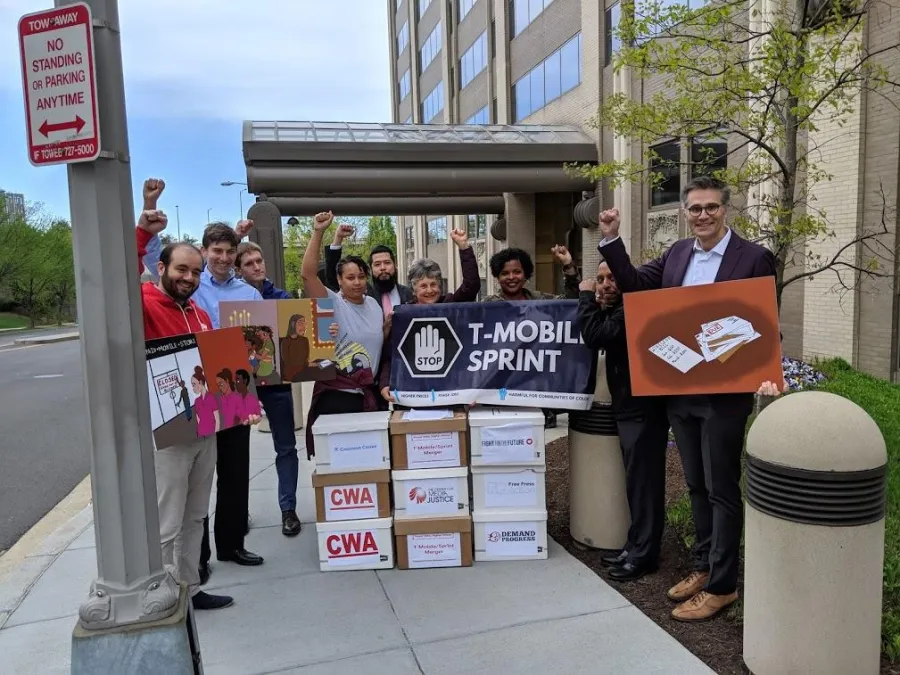

New CWA ex parte letter: T-Mobile and Sprint merger commitments fail to address anti-competitive harm and job loss

The Communications Workers of America (CWA) today submitted an ex parte letter to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) explaining why recently announced proposed commitments by T-Mobile and Sprint “fail to address the significant anti-competitive harm, spectrum consolidation, and loss of 30,000 jobs that would result from the merger” between the two companies, while their “unverifiable rural deployment commitments would leave as many as 39.2 million rural households without access to the New T-Mobile’s high-speed 5G network.”

The proposed divestiture of Boost as a mobile virtual network operator (MVNO) does nothing to alleviate concerns about merger-related job loss at retail stores. Because MVNOs operate many fewer retail stores than facilities-based prepaid carriers, the divestiture would result in store closings and layoffs.

The CWA letter also notes that the “so-called ‘voluntary contributions’ the Applicants proffer for failure to meet deployment commitments are toothless; not only are they tax-deductible as ‘voluntary contributions’ to the US Treasury, they represent an infinitesimal portion of the $74 billion 2018 pro forma revenue of the combined T-Mobile-Sprint.”

The CWA letter also highlights a keynote speech delivered by Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim in November 2017 before the American Bar Association’s Section of Antitrust Law, during which AAG Delrahim stated in part: “proper and timely antitrust enforcement helps competition police markets instead of bureaucrats in Washington, DC doing it,” and expressed deep skepticism of behavioral remedies, noting: “Behavioral remedies often require companies to make daily decisions contrary to their profit-maximizing incentives, and they demand ongoing monitoring and enforcement to do that effectively. It is the wolf of regulation dressed in the sheep’s clothing of a behavioral decree. And like most regulation, it can be overly intrusive and unduly burdensome for both businesses and government.”

CWA’s ex parte summary is available online here with key points summarized below:

The companies’ voluntary commitments do not resolve the competitive harm that would result from the merger

Merging T-Mobile and Sprint would lead to a substantial lessening of competition in at least two relevant antitrust markets: the overall mobile telephony-broadband services market and the narrower prepaid wireless retail services market. CWA’s new letter analyzes the companies’ voluntary commitments regarding future pricing and divestiture of the Boost prepaid brand:

The pricing commitment - a pledge to freeze rate plans for three years - is a purely behavioral remedy. As the Department of Justice has stated many times, behavioral remedies are “exceedingly difficult to craft, entail a high degree of risk of unintended consequences, entangle the government and the Court in market operations, and raise practical problems such as the need for ongoing monitoring and enforcement.” Pricing commitments are particularly undesirable. Price caps restrict the firm from competing on the basis of price, which is a central dimension of competition. Price caps may have the unintended consequence of discouraging the merged firm from lowering its prices. This is of particular concern in an industry in which prices have been declining and with parties that have positioned themselves as low price competitors. And the price commitment contains several loopholes that are likely to make monitoring and enforcement extremely difficult.

Divesting the Boost prepaid brand is “at best a partial remedy” and Applicants themselves “implicitly admit that this proposal will be insufficient to limit their merger-enhanced market power without significant behavioral conditions.” Divesting the Boost brand appears to be an effort to address the concern that the proposed transaction’s impact would fall disproportionately on lower-income customers who purchase prepaid services. However, the “divestiture” of the Boost brand is at best a partial remedy. It would not create a new facilities-based competitor and therefore would not replace Sprint as a market participant. Additionally, ongoing entanglements between a divestiture buyer and seller create a significant risk that the buyer would pull its competitive punches or that the seller would use its leverage to disadvantage the buyer. The Applicants themselves have identified a few of these levers. In the commitment letter, Applicants have stated that the agreement with a divestiture buyer would include promises not to engage in “unwanted discriminatory throttling, de-prioritization, or limitations on access to new network technology.” Thus, even as they propose what appears to be a structural remedy, the applicants implicitly admit that this proposal will be insufficient to limit their merger-enhanced market power without significant behavioral conditions. Finally, in early 2018, senior Sprint management did an analysis of a potential transaction involving Boost that raises serious questions about Boost’s value and competitive significance as a divestiture in this case.

The rural commitments are not verifiable, not merger-related, and would leave 40 million rural residents without access to T-Mobile’s high-speed 5G network in 2025

New rural deployment commitments are not verifiable and would still leave much of rural America without mid-band coverage. The companies’ Public Interest Statement showed that even under the best- case scenario, much of rural America would be left without the higher capacity mid-band coverage after the proposed merger. Now they make new and unverifiable deployment commitments, claiming that the New T-Mobile will provide mid-band coverage to 6.5 more rural households three years after the merger and an additional 6.1 million rural Americans six years after the merger than originally projected. The Applicants provide no explanation for the revised numbers. Even if the Commission were to accept the unverifiable new 5G deployment numbers, the best-case scenario would still leave much of rural America without the higher capacity mid-band coverage: And low-band coverage will be relatively constant regardless of whether the merger happens - the New T-Mobile’s low-band network would only service an addition 1.7 million users three years after the merger and an additional 1.1 million users by 2024 compared to stand-alone T-Mobile.

Speed commitments are overly optimistic. The Applicants promise to deliver 50 Mbps or higher to at least 90 percent of the rural population by year six, but would deliver mid-band to only 33.3 percent of that rural population—so even taking the spectrum commitment at face value without revised maps or engineering models, 33.3 percent of the rural population would only be served by low-band spectrum.

Drive test verification is insufficient. The Applicants’ propose to verify the speed benchmarks within nine months of the third and sixth annual anniversaries of merger closing through drive tests. The Applicants do not describe the drive test methodology they propose to use, nor do they commit to an independent third-party verification. It strains credulity to imagine that the New T-Mobile could perform accurate, verifiable tests to confirm that New T-Mobile customers in urban, suburban, and rural areas across the 50 states are receiving New T-Mobile service at the promised speed benchmarks under actual conditions.

In-home broadband. The Applicants claim that the New T-Mobile’s In-Home Broadband offering will “break the mold” for in-home broadband. If so, the mold must be a very small and leaky one as the Applicants’ in-home broadband would only be available to a tiny fraction of all US households.

The so-called enforcement “voluntary contributions” are toothless

The Applicants are free to promise the moon and the stars, because the “voluntary commitments” they proffer for failure to meet promised deployment, speed, and price benchmarks are as nebulous as the Milky Way. First, “voluntary contributions” are just that – they are voluntary. They are not automatic penalties, but rather subject to the discretion of the Applicants. Second, and more egregious, voluntary contributions to the US Treasury are tax-deductible, thereby significantly reducing any financial consequence to the New T-Mobile of non-compliance. Third, the Applicants’ themselves are responsible for data reporting, putting the fox in charge of the hen house. There is no provision for independent audit of the Applicants’ self-reported data. Fourth, the Applicants’ have access to a broad “get out of jail free” card to avoid any financial consequence for failure to meet promised benchmarks. The Commitment Letter allows the Bureau to “reduce the metric, extend the deadline or reduce the contribution amount” for circumstances beyond the company’s control, including “law or order of any government body” or “significant interruptions in the supply chain.” If the New T-Mobile faces “supply chain interruptions” as a result of a US ban on Huawei components driving up prices or creating equipment shortages, or if Congress or the Commission makes legislative or regulatory changes impacting the wireless industry, then the Bureau (not the full Commission) can change deployment metrics, deadlines, or contribution amounts. A loophole so big one can drive a truck through it. Fifth, the “voluntary contribution” rates are so small that they cannot serve as an effective deterrent. To take just one example, the “voluntary contribution” for missing a rural broadband deployment commitment by 10 million people represents only 0.34 percent of the combined companies’ 2018 pro forma revenue of $74 billion.

The commitment letter is silent on jobs

The impact of a proposed merger on employment is part of the Commission’s public interest analysis. CWA has provided the Commission with a detailed analysis that demonstrates the proposed merger would result in the loss of 30,000 jobs due to the elimination of overlapping stores and headquarters functions. The proposed Boost divestiture into an MVNO does nothing to alleviate concerns about merger-related job loss at retail stores. MVNOs such as Tracfone tend to operate many fewer standalone retail locations than facilities-based prepaid carriers. For example, while America Movil-Tracfone has more subscribers than either Metro or Boost, it only operates 258 standalone retail locations nationally as compared to 5,673 for Boost and 9,503 for Metro. The Applicants’ letter makes no commitment whatsoever to ensure that the transaction preserves US employment and protects jobs and compensation levels for current employees of T-Mobile, Sprint and their authorized dealers. Further, the Applicants make no commitment to return overseas customer call centers to the US, nor to cease their anti-union behavior by committing to complete neutrality in allowing their employees to form a union of their own choosing, free from any interference by the employer.

The Applicants are silent about spectrum divestitures

The Commission has long recognized that spectrum is a key input for wireless service and that “the state of control over the spectrum input is a relevant factor in its competitive analysis.” The proposed merger would massively exceed the Commission’s spectrum screen of 238.5 MHz. The spectrum holdings of the New T-Mobile – almost 300 MHz on an average basis – would vastly exceed the Commission’s spectrum screen and the holdings of other wireless carriers. The New T-Mobile would hold nearly three times as much spectrum per subscriber as Verizon and more than twice as much spectrum per subscriber as AT&T. The New T-Mobile would exceed the Commission spectrum screen in each of the top 100 counties in the United States, based on population, and in almost two-thirds (63.9 percent) of all counties in the United States. On a national basis, 92 percent of the US population, ore more than 284 million people, live in counties in which the New T-Mobile would exceed the spectrum screen. Yet, the Applicants fail to make any spectrum divestiture commitments.

CWA members oppose AT&T’s attempts to stop serving rural and low-income communities in California

CWA urges FCC to deny industry attempts to loosen pole attachment standards

CWA District 6 reaches agreement with AT&T Mobility